With the final episode of the fifth and last season airing on New Year’s Eve, Stranger Things has now officially come to an end. After spending several seasons with this world and its characters, it feels like the right moment to step back and look at what made the series work so well in the beginning, and why it slowly drifted away from that strength over time.

Stranger Things is, at its core, a very strong idea. And in its first two seasons, it knows exactly what it wants to be. That clarity is what makes those early episodes so effective and so memorable. What drew me in was never primarily the science fiction or horror aspect. It was the feeling. The series captures the early 1980s not as a backdrop, but as its emotional center. Kids on bicycles, walkie talkies instead of smartphones, landline phones, a world where you could disappear for hours without anyone panicking. That sense of freedom feels authentic, not nostalgic in a forced way.

This atmosphere is carried beautifully through visuals, music, and pacing. The 80s soundtrack works as an emotional anchor rather than decoration, while the recurring synth themes give the series a subtle, almost hypnotic tension. In the first two seasons, all of this comes together effortlessly.

I was born in 1973. That means I was exactly the same age as the kids in the series when the story begins in 1983, and I finished High school around the time the show ends in 1989. That alone explains why the series immediately felt familiar, almost uncomfortably so. Watching the series often feels like a parallel time travel. Not just back to the 1980s, but back into my own childhood. What the show depicts is not my idea of that decade. It is my lived experience. I spent endless days outside with friends, riding bicycles, roaming through woods, climbing hills in our neighborhoods, inventing adventures along the way.

Our parents did not track us or check in every hour. We simply disappeared for entire afternoons and came home when it got dark. We played cops and robbers using walkie talkies, feeling incredibly advanced at the time. Those devices were our version of high technology.

Even the music feels deeply personal. These are not retro references I discovered later. They are songs I remember from the moment they were released, tracks that accompanied me as I was growing up. Music was always with us. The Walkman was as essential as a smartphone is today. Cassette tapes in our pockets, rewinding with a pencil, fast-forwarding to the right track, recording mixtapes at home. Cassettes. What a time.

And it was not just the music. The clothes, the hairstyles, the way we dressed for school parties, the awkward first dances, the first kiss. All of it feels instantly familiar. Stranger Things does not recreate these moments as nostalgia. It reflects them as they actually were.

That is why Stranger Things (at least the first two seasons) resonates so strongly with me. It does not just recreate a decade. It mirrors a journey I lived myself.

Mystery works best when it is not explained

The real strength of the early seasons lies in restraint. There is something foreign and unknown. Another dimension. Creatures that cannot be understood. You do not know where they come from, what they want, or how they work.

That uncertainty creates suspense. Fear does not come from constant action, but from suggestion. From the sense that something is wrong, that something is lurking just beyond what you can see. The Upside Down is not a defined system at this point. It is a mood, a threat, a place that does not follow our rules. That is exactly why it works.

A gradual loss of focus

From around the third season onward, the series slowly starts to drift. Not suddenly, not catastrophically, but noticeably.

Episodes become longer. The plot grows more complex. New characters and side stories are introduced. Many of these characters are well acted and often enjoyable to watch. But more and more, they feel unnecessary. Some appear, take up a significant amount of space, and then disappear again after a single season. Looking back, it is hard not to ask why they were needed in the first place.

Not every new figure deepens the story. Some feel like additions made to expand runtime rather than to strengthen the core narrative.

At the same time, the original concept no longer seems sufficient. The Upside Down on its own is no longer enough. Suddenly, there is yet another realm, the Abyss, connected through a wormhole. And of course, it is not simply there. It is created by humans, explained in detail, mapped out but not justified. Why was it created? Unanswered.

What once felt like an unknowable other world becomes part of an increasingly engineered system. The mystery is expanded, but not deepened. Instead of adding tension, this additional layer further dilutes the original idea. In the 1980s, people were able to construct something like this, but apparently had no control over it. It looks very much as if the production team was desperately searching for content for the series and had to constantly come up with new theories and plot twists to keep viewers excited, but this was at the expense of the story and quality.

When more becomes too much and monsters become human

At the same time, the storytelling itself changes. Mystery gradually turns into action. Suggestion turns into explanation. Suspense turns into spectacle.

The series begins to define its own mythology in ever greater detail. Dimensions gain structures and hierarchies. The monsters change constantly, not only in appearance and numbers but in meaning, and in how they exert control over their victims. What was once alien and unknowable is slowly rationalized and explained. This is where the main problem lies for me.

In the end, the threat is no longer something truly foreign. It becomes human. A psychopath with supernatural abilities. A character with a backstory, motivations, and a clear origin. While the antagonist is influenced and possessed by an otherworldly intelligence, it is ultimately a choice he accepts. That decision shifts the nature of the evil itself. What could have remained alien and incomprehensible is once again rooted in human intent.

The introduction of this central human based villain also retroactively weakens the mystery of the first two seasons. What once felt open, unsettling, and undefined is suddenly reframed through a new lens. The story is repositioned yet again, adding another layer of explanation that feels unnecessary. The narrative begins to revolve around a grand, carefully constructed master plan, one that is highly technical in nature and, in many places, difficult to follow logically.

Instead of deepening the myth, this new perspective makes it more confusing. It demands more and more explanation, and yet, on closer inspection, many of these explanations do not truly hold together. What once worked through atmosphere and uncertainty now relies on construction and justification.

That shift fundamentally changes the series. Evil is no longer something unknown, but something man made, or at least something man has chosen to shape by embracing an alien force. The mystery is no longer open, but resolved. For me, this takes away much of the power of the Upside Down. Why does everything need a human cause? Why cannot a monster simply remain a monster? Why must a foreign world always be fully understood?

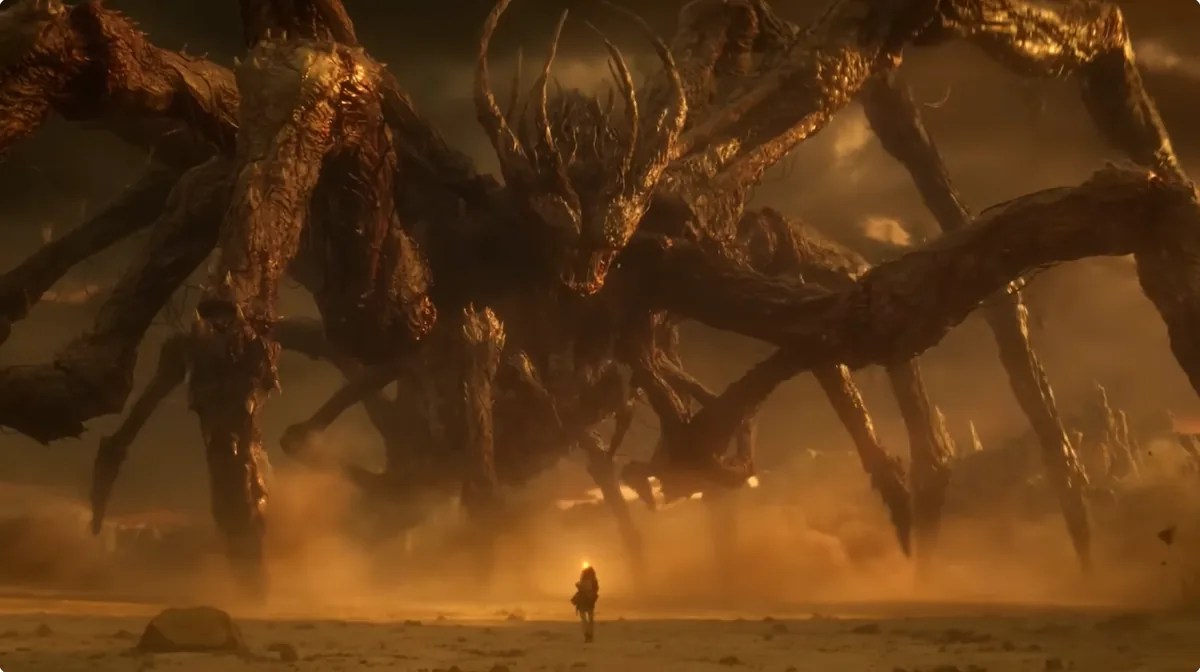

There is also the alien presence itself. The Mind Flayer, formed from drifting particles into a gigantic living shadow, was one of the most powerful and frightening ideas in the series. A shape without a face. A presence without a body. It felt ancient, intelligent, and completely beyond human logic. But in the end, even this entity is given a physical form, like something out of a bad Godzilla movie, directly linked to the human antagonist at its core. By becoming tangible, it also becomes vulnerable. And in doing so, it loses much of what made it truly terrifying.

Why could it not remain a shadow? Why did it have to become something that could be fought? Sometimes, the most powerful monsters are the ones that never fully step into the light. Especially in science fiction and mystery, there is great strength in leaving things unexplained. In allowing ambiguity. In trusting the audience to live with unanswered questions.

Strong characters, weaker core

To be fair, character development continues to work well in Stranger Things, even in the later seasons. The characters grow up, evolve, and face more complex emotional challenges. Friendships change, relationships become strained, and loss feels real. This part of the series remains convincing and often genuinely moving.

However, as more and more characters are introduced, there is less time to fully explore each individual arc. Development becomes fragmented, spread too thin across an expanding ensemble. When many of the protagonists are brought together in the same scenes, the dialogue sometimes feels forced, as if everyone needs a line simply to justify their presence. Instead of deepening the characters, these moments can flatten them. That feels like a missed opportunity.

Strong characters alone are not enough when the narrative core becomes overloaded. When more ideas, more threats, and more explanations are layered on top of each other, clarity is lost.

The Magic of the Unknown

Stranger Things is at its best in its first two seasons, when it combines atmosphere, time period, and mystery with confidence and restraint. It is emotional, tense, and genuinely mysterious without needing to explain itself. Later on, it loses that confidence. It wants to be bigger, longer, and more complex. In doing so, it sacrifices something essential. The magic of the unknown.

Sometimes, a monster from another world is strongest when we do not know where it comes from. And sometimes, a story loses its spell the moment it decides to explain everything.

Just my first 5 cents in the new year.

Alex